Between Land & Water

Walking the Littoral Line

There is a theory that life began in a salty sea, perhaps near a geothermal vent or in a rock pool.’ Filmmaker and artist Jane Darke co-made The Wrecking Season (2004), a film about beachcombing in North Cornwall with her husband, playwright Nick Darke. Her film The Art of Catching Lobsters (2005) chronicles the days and weeks following Nick’s untimely death. Here she explores the littoral zone and our relationship with the ever-changing coast.

An empty beach is the best place I know for freeing my shackles – it’s a timeless occupation. I’m 60 years old and these days I swim just as well as I can walk. Whether I’m a creature of the land or of the sea I’m not always certain. I walk the line between them both and as I do I feel a connection with others who did the same far back in time. I live on a beach on the north coast of Cornwall and I’ve got to know and understand the shore – it’s become my place of work.

On the beach I read the lines that remain as sediments shift. I watch the sand build up and sweep out with the wind and storms. I collect what lies on the strandline, try to interpret everything the sea has carried from elsewhere and keep a record of anything interesting. The objects left behind tell their own stories – a plastic bucket, part of a violin, a dead swan or a tape measure. Through these collections of the sea-worn, I try to understand the world. This is what my book Held by The Sea (Souvenir Press, 2010) is about but it’s also about the grief I felt when my husband died and how the sea saved me. I started to feel a part of the land and sea in a way that I hadn’t before:

Wading through water is like being in a boat. At three foot deep my eyes are about the same height as they would be if I leaned over the gunwale. I disturb the fish either way. If I wade I can touch the weed or reach down to inspect a hermit crab. My hand is magnified, so are my feet and if the sun is shining then the ripples make lines of light that run over my skin. Everything in this world is smaller than me. I am Gulliver. I climb to the top of the islands and look down into the great pool, shades of green and blue darkening to the bottom where weed rots, buried in the sand. Bubbles of gas burst on the surface, at beach level the smell of rotten eggs is strong. A line of mullet circles, trapped between the tides. Another of sand eel crosses their path. Above, sun light catches along their length, for a second. The mullet, scattered on the bottom, have found something to eat. Long strands of weed cast shadows on the sea bed that wave with movement of water.

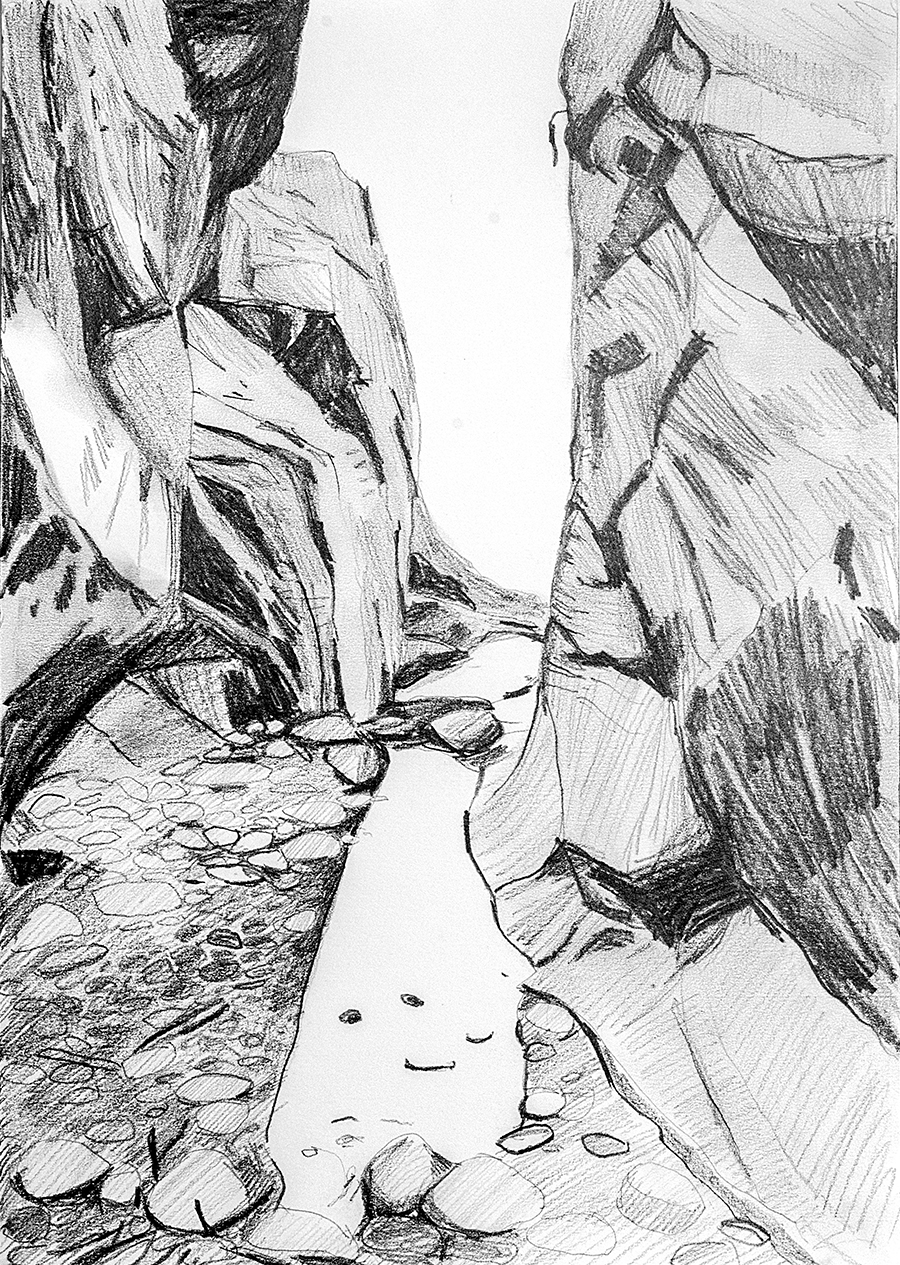

If I turn from here I’m looking out to sea. The back of the islands fall away above and below the surface, the rocky seabed supports a forest of kelp. In early spring, the sea gets up and waves rip it off the rocks. This is the weed that covers the beach sometimes, rots down to make the dunes.

The ‘littoral’ is any shoreline where sunlight reaches through water to the sediment layer below. Change is at the heart of the littoral – a place where water meets land is in a constant state of flux. There is a variety of habitats – the muddy fringe of a volcanic lake, inhabited by ducks, a landscape of rocks and pools at low tide, a line of beach covered with ocean debris left by the high tide. Wetlands, cliffs, estuaries, river banks, shingle banks and rocky foreshore sometimes permanently underwater – salty or fresh, all these are part of the ‘littoral’. It’s the ecological border between land and water; a delicate, finely-balanced place. I live near the littoral, by a sandy beach where the highest spring tide comes right up to the dunes, and at the lowest falls back to uncover rarely-seen rock pools below the cliffs.

The ‘littoral’ is any shoreline where sunlight reaches through water to the sediment layer below. Change is at the heart of the littoral – a place where water meets land is in a constant state of flux. There is a variety of habitats – the muddy fringe of a volcanic lake, inhabited by ducks, a landscape of rocks and pools at low tide, a line of beach covered with ocean debris left by the high tide. Wetlands, cliffs, estuaries, river banks, shingle banks and rocky foreshore sometimes permanently underwater – salty or fresh, all these are part of the ‘littoral’. It’s the ecological border between land and water; a delicate, finely-balanced place. I live near the littoral, by a sandy beach where the highest spring tide comes right up to the dunes, and at the lowest falls back to uncover rarely-seen rock pools below the cliffs.

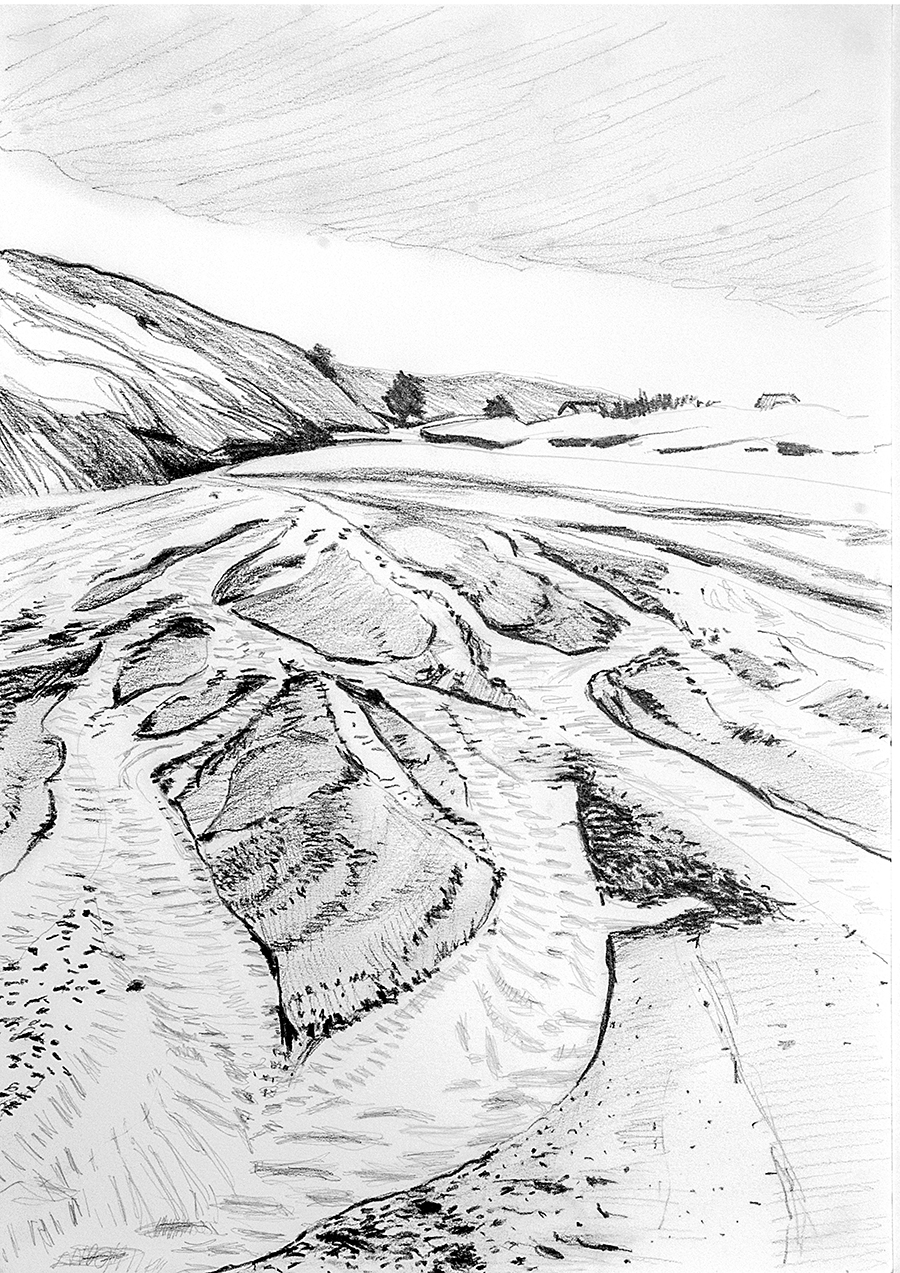

Through the seasons of the year I watch the rain and sea sculpt the land. The beach I walk on is still being made by the stream which cuts a valley into the slate and takes small stones and clay down to the waterline where the sea dismantles the cliffs. There are places that seem constant but they are high up, out of the reach of water, and I go there to look down on the changing world below. I like to be alone so I can travel in time, both geological and human.

In the past many people worked the shores of Britain and Ireland – coastal waters and lakes were populated by boat builders, barge operators, revenue men, ferrymen, fishermen, reed cutters for thatch, willow cutters, poachers, washerwomen, millers, dyers and more. The poor depended on the available food and driftwood and crofters gathered seaweed for fertilizing the land and feeding cattle. There are still plenty of cultures worldwide that live off what they find on the edge, but for most the littoral has changed from a border to a gap, an empty place where imagination can run wild and where people play.

I wake up, get out of bed and pull back the curtain to look out of the window at my constant companion, the sea. It’s just below me and at high tide it is about 30 metres away. My house is just above the dunes that shift slowly towards the sea. Along the road at the top of the beach, houses built in the 1920s form a barrier where sand, that had previously been blown straight up the valley, piles up. There’s an old map that shows mean high water much further up the valley, the sand forming a ridge where people walked, then rode, now drive, across the top. Once the road was established, and walls built either side, it changed the way the sand and sediments moved up and down the valley. The land behind the houses, now lower than the road, is a reed bed and water meadow with a stream running through the middle. The Environment Agency projections for sea level rise, over the next 50 years or so, show the sea sweeping away the bridge where the road crosses the stream, and filling this low area of marshland behind. The houses will sit on a spur of land, for a while, until the sea takes them too. There will be no permanent coast road through the settlement I live in.

When I first arrived here nearly 40 years ago, I thought it was all permanent, fixed. I didn’t understand the mobility of land adjacent to water. Now I think about it a lot. When I go to Suffolk I see great shingle banks which move every year. The sea there takes land daily, slicing off sections of orange sandy soil like gingerbread loaf. When I travel by train from London to Cornwall I see, during some winters, the land turn into a lake where houses built centuries ago sit proud on higher land. Places I can get to now at low tide will be permanently under water by the end of the century. The sea level is rising and my home is in the way.

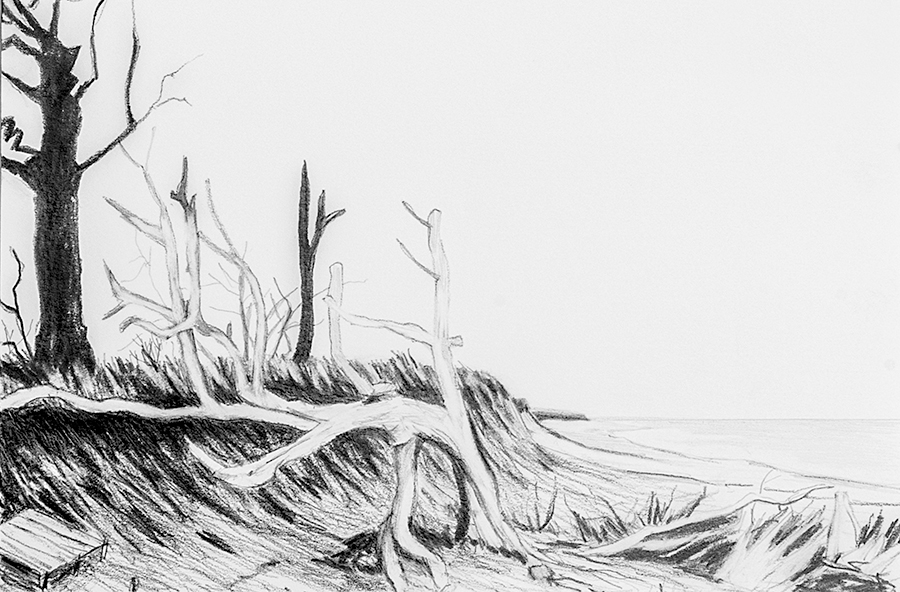

There are often storms here between October and April, and in the winter of 2013 there were a succession that built over the weeks from December through to February 2014. On Valentine’s Day the sea was the biggest I’ve seen it – immense waves seemed to move in slow motion with the weight of water they carried, hammering into the cliffs and taking the front layer of slate clean off. Rocks suspended in the waves ground into surfaces scouring out new pools. Towering waves on a huge spring tide cut the front face off the dunes and took thousands of tons of sand straight out to sea. The upper beach level was left three metres lower by the end of the month and when the storms subsided it was transformed – the sea was a milky soup of ground-up plant and animal matter, the weed and other marine life gone from the beach. Then gradually through the spring the algae returned, the mussels re-seeded and by midsummer the rock falls had been buried by sand and the pools were re-inhabited.

I photographed the beach through that year to keep a record of the new changes. The edge of the dunes, which had been left a vertical drop of three metres, gradually formed a slope towards the sea again. The sea had taken the sand but old plastic buried in the dunes was revealed. I found crisp packets from the 1970s and 80s, a 1950s Parker pen and a blue ‘Noddy’ toothbrush like one I’d had as a child. A French fishing boat ran aground in the same storm and the crew were rescued by the Padstow Lifeboat and a Royal Navy Search and Rescue helicopter, but in the past you might have been wrecked in a cove and never found. Ships have traded along this coast for at least 2,000 years, for tin and copper and stone, and I have found the ribs of oak ships, the wooden pegs which held them together and a copper plate milled in Swansea from the hull of a warship. I have also found six human teeth exposed in the turf by backwash from the waves. Who did they belong to? A sailor from a ship lost a few centuries back or someone from a much earlier time?

For a long time now I’ve felt part of that older world. I find stone tools, blades for catching fish and scrapers for skins and removing scales poking out of the turf edge above the cliffs. I found part of a human skull in the sand below my house, very old and fragile, probably from a burial on the cliff. Volume 25 of Cornish Archaeology, published in 1986, has much to tell about the people who lived here in the Bronze Age. There are remains of these people everywhere on the north coast and they relied on the easy pickings to be found in the littoral. On several beaches there’s a layer, under the sand and stones, of clay. This clay was at the bottom of pools or lakes which formed just after the last ice age, so about 7,000 years ago, when the sea level was also rising. (In the middle of the ice ages, when much of the water on the planet was lying frozen on the land, the sea level was one hundred metres lower than it is today.) Under this clay are the remains of trees and among them hazel nuts. Hazel nuts can be found on most beaches as they are washed down the rivers. But if you find one on the strandline, you can’t tell if they are fruit from this year or from a pale summer thousands of years ago at the end of an ice age.

As the tilt of the Earth’s axis changes, there is a wobble known as the Milankovitch Cycle – the Earth’s orbit of the sun is an ellipse which is ‘eccentric’ because of the gravitational pull of Saturn and Jupiter, and because of the uneven tidal forces caused by the gravitational pull of the sun and moon on Earth’s watery surface. Studies suggest a close connection between patterns of ‘eccentricity’ and of glaciation with current thinking suggesting that we are currently in the middle of an inter-glacial period.

Recently, I’ve been spending more time in other parts of the world – in New Zealand where beaches are still covered with trees  and wood from endless forest, as ours once were. I’ve driven up the Rift Valley in Kenya, where some of the oldest bones of our early hominid ancestors were found. I crossed into the West Bank, ancient Palestine, part of what is known as the Fertile Crescent, the birthplace of agriculture, where wheat, barley, lentils, flax, cows, pigs and goats were first farmed. Palestine is itself composed of marine sediments – limestone laid down on sea beds 100 million years ago. One million years ago several early human-like species, in what is now Africa, endured or were wiped out by a series of ice ages. Ice sheets covered much of the northern hemisphere for tens of thousands of years then melted away leaving grass land. Before another ice age descended the forests grew, and as ice stretched across continents, the sea level fell and rose, sometimes metres in a decade. So our ancestors migrated, following food to survive. Archaeological evidence puts them at Gona, near the coast of Ethiopia, 2.5 million years ago. Between 1.2 million and 0.8 million years ago sediment samples show that sea levels dropped and two huge land masses of shallow continental shelf were exposed – one in Western Europe around the Mediterranean, Britain and Ireland, the other extending from the east coast of Africa, along the coast of India and down to a vast area around the coast and islands of Indonesia and China. At the same time grass grew in the eastern Sahara and rivers were swollen by melt water from glaciers in high regions. Our ancestors spread out into the newly available land until the next period of glaciation forced them back or cut them off.

and wood from endless forest, as ours once were. I’ve driven up the Rift Valley in Kenya, where some of the oldest bones of our early hominid ancestors were found. I crossed into the West Bank, ancient Palestine, part of what is known as the Fertile Crescent, the birthplace of agriculture, where wheat, barley, lentils, flax, cows, pigs and goats were first farmed. Palestine is itself composed of marine sediments – limestone laid down on sea beds 100 million years ago. One million years ago several early human-like species, in what is now Africa, endured or were wiped out by a series of ice ages. Ice sheets covered much of the northern hemisphere for tens of thousands of years then melted away leaving grass land. Before another ice age descended the forests grew, and as ice stretched across continents, the sea level fell and rose, sometimes metres in a decade. So our ancestors migrated, following food to survive. Archaeological evidence puts them at Gona, near the coast of Ethiopia, 2.5 million years ago. Between 1.2 million and 0.8 million years ago sediment samples show that sea levels dropped and two huge land masses of shallow continental shelf were exposed – one in Western Europe around the Mediterranean, Britain and Ireland, the other extending from the east coast of Africa, along the coast of India and down to a vast area around the coast and islands of Indonesia and China. At the same time grass grew in the eastern Sahara and rivers were swollen by melt water from glaciers in high regions. Our ancestors spread out into the newly available land until the next period of glaciation forced them back or cut them off.

About 160,000 years ago we know that a group of early humans was living in a cave on Pinnacle Point near the Cape of Good Hope on a diet of shellfish. How did they get there? Perhaps they had travelled through flooded forest, lost a few of their family to predators. Did they sit on branches over the water and wade when they needed to? Did they smell the sea before they saw it, wonder at the sound of it, think it was another set of rapids? When they came to the shore would they have been surprised by a horizon full of blue water, and seen lakes that seemed to stretch forever? Did they squat down in the surf, scoop up a handful of cold water to drink and spit it out because it was salty?

The beaches then were covered in wood, from the nearby forest but also wood that had drifted from other continents. Sun-bleached branches, tree trunks and roots were everywhere. I imagine them clambering over and under, sheltering from sun and rain, finding crabs and insects in the layers of natural debris trapped in-between. Fur seal pups would also have been sheltering there in the breeding season, waiting for their mothers to return, and they would have been easy to kill with a branch or scavenge when washed ashore, dead or starving after a gale. They would have found beached whales and learned over millennia to use every part.

Our ancestors learned from the littoral. They didn’t stay for long in one place but followed the shoreline, sometimes wading up an estuary where they also picked up birds’ eggs from nests in the reeds. In lakes they found water lilies and fresh-water fish and perhaps they followed the rivers inland for a while until the forest became dark and dangerous. But once they had found the sea they always turned back to the coast where it was relatively safe and the food easy to find. On the beaches and cliffs there were nesting birds with eggs, plants with roots ready salted by the sea spray, shellfish and fish caught in tidal pools. If this is where we started to be ‘hominin’, a truly human species, then living by water is literally written into our DNA.

Of all the species that have ever lived on the earth 99.9 per cent are extinct, whether through era-ending meteorites hitting the earth, huge volcanic eruptions that have ushered in thousand-year winters or through poor stewardship. We think that we have exploited nature but now we know that nature also exploits – ice forms and melts, the seas warm and cool, expand, contract, the sea level rises and falls, the currents change, even the land is moving. Continents will slide around the globe for as long as the boiling heart of it throws up magma.

The dunes shift, the cliffs fall, the weed is torn off, and new growth starts up before old weed has shed its spores. The river moves this way and that across the bay. The sand surface has undulations which change daily reflecting the patterns of waves and ferocity of wind. And the rocks on the shore have two separate eco systems – one exposed to the light and waves, another underneath sitting in the sediment. And when the sea turns the rock over, everything changes for life on the other side. Nothing is permanent.

This article was first published in Edition Two of Elementum Journal

Jane Darke is a documentary director, painter and writer. She made a film about Atlantic debris with playwright Nick Darke about their collection of found objects and connections made through them with the eastern seaboard of the Americas, as well as Cornish fishermen and wreckers, The Wrecking Season, 2005. It was the first film to be broadcast to mention plastic pollution of the seas. The Art of Catching Lobsters, about grief, was made after Nick died in 2009. Her most recent film was about the Poet Charles Causley (2017). All were broadcast on BBC FOUR. Her book Held by the Sea was published by Souvenir Press in 2010, about the healing power of landscape. Jane has also made several radio programmes for BBC Radio 4.

Jane Darke is a documentary director, painter and writer. She made a film about Atlantic debris with playwright Nick Darke about their collection of found objects and connections made through them with the eastern seaboard of the Americas, as well as Cornish fishermen and wreckers, The Wrecking Season, 2005. It was the first film to be broadcast to mention plastic pollution of the seas. The Art of Catching Lobsters, about grief, was made after Nick died in 2009. Her most recent film was about the Poet Charles Causley (2017). All were broadcast on BBC FOUR. Her book Held by the Sea was published by Souvenir Press in 2010, about the healing power of landscape. Jane has also made several radio programmes for BBC Radio 4.

She now works and exhibits at Tregona Chapel, St Eval, on the North Coast of Cornwall, where she curates St Eval Archive a collection of recorded memory and digitised photographs, and lately a herbarium, of the parish of St Eval, gathered by herself and partner Andrew Tebbs. There they hold teas and workshops for the community.

Jane is currently working on a new film about Nick Darke’s influence, since death, on the creative lives of others. She is crowdfunding to make the final interviews and to edit the film. The money raised will be used for publicity and sending it to film festivals.