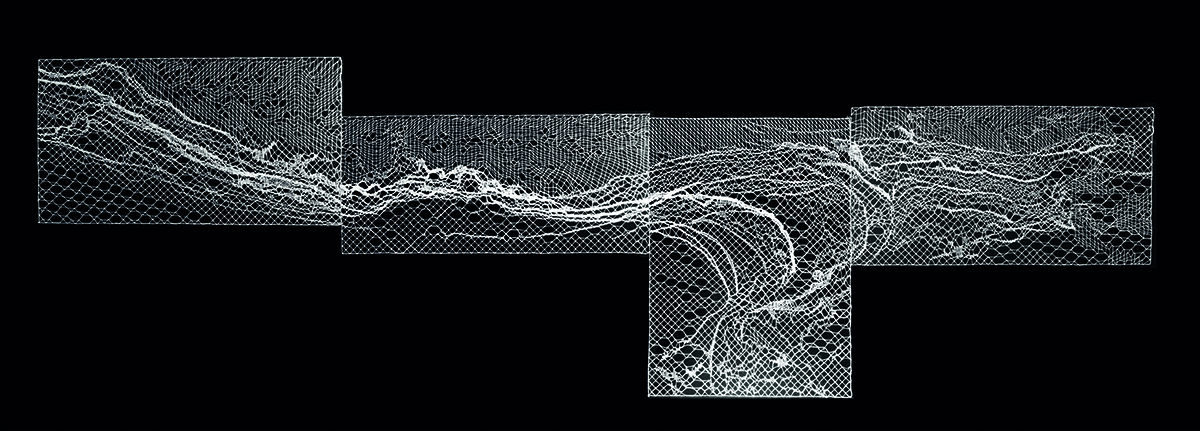

Seableed

A Quest To Capture a Shifting Terrain in Lace

Words: Jane Atkinson | Photography: Jay Armstrong

Inspired by a daily walk on Stanpit Marsh near her home in Dorset, Jane Atkinson uses her ingenuity and a life’s experience working with thread and bobbins to recreate the delicate formations caused by tidal swirls and eddies into a panel of contemporary lace that speaks of the fragility of life and landscape.

I need to wind more bobbins with thread. There are already about 250 on my lace pillow, but I’ve reached a point where I could do with more. I’m not following a traditional pricking – instead I take my lead from a sweeping festoon of pattern I saw floating on the marsh some time ago, which I’ve sketched on board and laminated. I’m having to draw on all my years of making to translate what I saw into a panel of contemporary lace. I walk the marsh most days, but in thirty-five years I’d never seen anything like this. The surface of the water was charged with fine threads of what looked like thin white paint bleeding out from rotting seaweed. The wind had swirled it into undulating gauzy tresses, diaphanous ribbons hair-fine and densely textured. I have seen other arresting conformations on these salt pans – etiolated clouds of bubbles, eddying traceries of dust. Frequent visits over several decades have built memories to which I have added a photo diary – but this is new.

The philosopher Frederick Nietzsche detected something he named ‘eternal recurrence’, where an anticipated view creates a resonance shared by both the landscape and the returning walker. Many others, including Aristotle, have walked the same path every day, finding solace and renewal, a space to think. Each day I take the same route but, on the marsh, yesterday’s land could be today’s water. My walk crosses different terrain depending on the state of the tides and moods in the weather – parts of my route are intermittently submerged as the waters rise and fall. This piece of land is in daily conversation with salt water – here in Christchurch harbour we have double tides, as does much of the south coast of England, due to the bottleneck effect of the Dover Strait.

Crossing through a gate from suburbia, the first view is of a low sward interlaced with pools and runnels – minute differences in the height of the water that fills them tell me how difficult the path may be to traverse further on. This part of the path is a causeway that runs beside a higher level of ground that is mainly used by dog walkers. It also rolls with dips and bumps – previous generations thought landfill would deliver municipal buildings and playing fields, but the underlying landscape reasserted itself like the pea beneath the princess. When we moved here, our old bungalow had four open hearths, and this area holds the ‘fly ash’ they and thousands more generated.

Past the poplar and willow windbreak at the end (sadly snaggle-toothed since around a third blew down in this decade’s storms), and the rest of the marsh opens out. There are mudflats where migrant birds feed and roost, and low vegetation – swathes of reeds and rushes – is patrolled by grazing ponies. The path leads down to the confluence of the Dorset Stour and the Hampshire Avon rivers, which flow into Christchurch harbour. Between the marsh and this natural harbour is Grimmery Bank, a spine of high ground that lies between the water and the land.

Crouch Hill in front of me crouches higher than its surroundings, surmounted by the wreck of a Beaker barrow abandoned by the archaeologists who bore off the Bronze Age burial to the local museum. At times, the waters rise to cover the whole marsh, but never this feature. A Bronze Age causeway – built when the sea was lower and further away – leads to the hill where seven-thousand-year-old flints found in the sand of the hill bear the percussion marks of Mesolithic knapping. There I found another type of stone, one with a crazed pattern on its grey surface. I learnt that these were Stone Age cooking stones, which would have been baked in a fire and then dropped scalding hot into a container of cold water to boil. Once, from a more recent age, I also found round shot possibly used for wildfowling or smuggling. The people who occupied this area over millennia past lived from what land and sea delivered.

The pools along the path have fuelled my lace experiments, offering beautiful air pockets contoured beneath iridescent ice crystals with sunlight glinting off the surface or refracted beneath it in golden ‘caustic’ ripples. I translate these into panels and hangings. Traditionally, lace is carefully plotted on rigid grids, but the marsh has inspired me to try fluid grids and extempore interpretation. Tristan Gooley, in his book How to Read Water, explains the factors that determine ripple shape and frequency – how they reflect, refract, diffract. I’m fascinated that people in cultures other than my own read water – I’ve been trying for years.

But subtle changes during recent decades have overtaken me. Thick ice is rare now, and spectacular crystals seldom get the several days of freezing weather they need to develop. Down by the river at Grimmery Bank, where I found the convolution from which I’m now working, the water is warming so much in summer that new seaweeds are taking hold. I suspect the one I saw rotting that day was the Pacific red seaweed Gracilaria vermiculophylla, brought into the harbour by visiting leisure craft last summer. It stank out the village when it died off in the autumn – I had never smelt anything like it. Thick mats of weed covering the mudflats prevent small waders from feeding, and rotting weed removes the oxygen from the water that other species need. It is also a pollution indicator.

Whereas I once walked year-long in shoes, I now need boots throughout the winter and on spring tides. Liquid incursions once merely inconvenient have had to be surmounted with ever-more-substantial boardwalks. Projections show we are lucky still to be walking here – the next generation will lose the opportunity as sea levels rise ever faster. Eastern philosophy reminds us that everything is impermanent, but we don’t seem to be registering clearly enough just how fragile our landscape is. Apparently, something as inconsequential as the temperature of the room in which we read climate-change statistics affects how seriously we take them. If everything appears normal, we can be tempted to disregard the evidence.

Other walkers pass unheeding as I crouch with my camera, attempting to capture this delicate moment – often shifting, disappearing even as I press the button. I later ponder its significance as I preserve its shape in thread. Back towards the edge of the marsh, as I make my way home along another causeway, reputedly built to train soldiers of World War I to practise hauling artillery across Flanders mud, I pass the pool that inspired my most adventurous set of lace panels. It held a huge pattern of bubbles, likely to be oxygen and nitrogen, sent up by the encroaching tide from roots in already waterlogged, oxygen-poor soil.

The landfilled recreation ground I cross at the end of my walk is breathing methane, eighty-six times more toxic for global warming than carbon dioxide. Salt marsh is now recognised as a carbon sink, locking carbon away for thousands of years (look at the way sodden artefacts in the Fens have lasted since the Bronze Age). If we had let well alone, we might be in a better state now, for when we drain wetlands we release all that stored carbon as well as denying the planet the extra blessing of lush plant growth that sequesters carbon from the air. Friends of the Earth calls the 5,000 coastal landfill sites around the UK a ‘ticking time bomb’, which will need to be protected as the sea rises. The fly ash under my feet (dumped on bare ground with no liner) could contain around eighteen heavy metals, including arsenic, which is toxic to humans and no doubt to the fish in the river and the invertebrates in the mud on which the birds feed.

By selecting images to turn into lace that capture visual evidence of climate breakdown, I am creating conversation pieces that make it more real, both for me and I hope for the audience at my exhibitions. I am now discovering that my lace pieces can take this discussion public.

That is, if I can manage to complete it – and it may be that I can’t with this pattern, that I’ve reached the edge of my capabilities, this being the piece that finally takes me out of my depth. On this piece, there are times when I can only work for a short period before I face an impasse, when I get the unbearable urge to do the ironing, to back off, when my brain hurts with effort. Winding new thread onto old bobbins shifts the pressure to another day.

These patterns take me away from my roots in traditional fine lacemaking but back towards them, too. I’ve always tested the margins of what it’s possible to construct, imagining designs into which I could weave the most air, finding the limits of the medium and of myself. At one point, I was making the largest pieces of lace I could manage as quickly as possible – banners, wall hangings, scarves – in threads the weight of four-ply knitting wool, thick enough to wind onto bobbins the size of pepper mills. Now I am allowing myself to linger over panels of detailed work in fine threads again, still spread over a wide area but suitable for the resurrection of my Victorian bobbins.

Working from Stanpit Marsh has set physical boundaries that have enabled me to push the limits of my lacemaking and free up my creativity. They have also given me independence and identity as a maker. For years I walked past a succession of fragile, remarkably lace-like formations but was baffled as to how to capture them in thread. One day I decided that I would find out how somehow, and if I failed I would simply keep trying. Maybe age has something to do with it. I have lived here since I was thirty, and I have been walking the marsh daily since I was fifty. Reaching sixty, I had published several decades’ worth of experiments on turning lace into an art form – but then what? Standing at the funeral of a much-loved contemporary, wishing we had both achieved our individual dreams, I wondered what I had to lose by pushing for mine, into unknown territory? The marsh had inspired me for years and there was nowhere I knew better – perhaps it could draw me further?

The first few inches of ‘Seableed’, my response to the pattern I saw floating on the marsh water last summer, now cover my lace pillow. It might look impossibly complicated, but it’s more straightforward than you think. Using four bobbins at a time, a pair in each hand, the lacemaker uses a binary system – think plain and purl in knitting, or 1 and 0 in computer code. With lace it is ‘half-stitch’ and ‘whole-stitch’. Everything is a combination of these two things. For whole-stitch, you cross the two centre bobbins, left over right, then twist the left-hand and right-hand pairs right over left, then cross the centre bobbins again. This weaves the two pairs of threads through each other. Half-stitch leaves out the last movement.

Pins anchor the work in place as I weave and twist my way over a pattern. In most lace I know exactly what I am doing – it gets more difficult when I make it up as I go along, creating what is known as ‘free lace’. I am following the shapes suggested by the pool, keeping an eye on my photo for clues on what to do next. My problem comes at the point when the wind snags the swirling pattern and I suddenly need to change direction or magic up more threads. I like being confronted with problems that force me to invent, refresh or research new methods. I would not miss this for the world.

There are points when I truly do not know what to do next. I identify with descriptions of cavers hanging over a dark hole on a length of rope and I can liken it to mountaineering, where you might edge along a precipice before your ledge peters out and you must retreat – I spent half of yesterday going backwards. I don’t aspire to climb Everest, but casting assorted fears aside at my lace pillow – doggedly pressing forward, evaluating, retreating, trying again – has opened up more new opportunities than I could have imagined. This is lace unlike anything I have done before. I am learning so much, yet all that matters is the present moment – for, as I nudge sixty-eight, the future is always uncertain.

The work is confronting me with essential questions – above all, questions concerning my personal quest for eternal recurrence. My local inspiration has always been ephemeral, but now it is in retreat. Sadly, this includes trees I have studied for foliar hangings and also birds – some populations, such as dunlin and ringed plover, have declined on the marsh by three quarters over the past twenty years. My lace allows me to confront people with these ‘inconvenient truths’.

Back to winding new bobbins. I handle them with extreme care, using a delicate touch responsive to each thread in turn, some as fine as hair. The pencil-slim bobbins I use are made of bone and wood, sometimes inscribed as love tokens (‘Dear Hannah’), as tombstones (‘Ann Brum, Radstone, 1840’), for the birth of a baby or even to commemorate a public hanging. It was by chance that I came across ‘Joseph Castle, hung 1860’. Joseph, who murdered his wife Jane, was hanged in Luton and his in-laws held a memorial event at which participants were given commemorative bobbins. I have not used this one for decades but I hang it on my pillow with huge satisfaction, coming back to my roots in traditional lacemaking after long abandoning the fine traditional Bucks point and Bedfordshire laces for which the bobbin was made.

Bobbins are ‘spangled’, threaded on wire with beads. Everyone (even Queen Victoria when shown lacemaking at the Great Exhibition) asks the same thing: do these tell you which one to use? No, they just help to tension the thread, balance the bobbins in your hand and stop them rolling. A pretty pillow is part of the pleasure of lacemaking, for you do not look at the bobbins when you use them – your entire attention is focused on the work, on the twitch of the right thread as you lift it, and the way it weaves through the next.

The British artist David Hockney has talked of ‘seeing with memory’, where the significance of what appears today is sharpened by the image lingering in our minds from yesterday. Tension is the basis of lace construction, the pull and push of threads steadied by pins as work proceeds, woven and twisted to create figure and supporting ground. While old laces are underpinned by rigid, geometric grids, nature’s tensions stretch like chewing gum, a ballet of opposing forces that leaves ephemeral traces. It is those that have come to intrigue me in my attempts to capture the land as it burgeons, decays and transforms.

'Seableed' was first published in Edition Four of Elementum Journal

Jane Atkinson is a contemporary lace artist, designer, maker, tutor and author. She lives and works in Christchurch, on the south coast of England.

Image of Seableed: Peter Smith