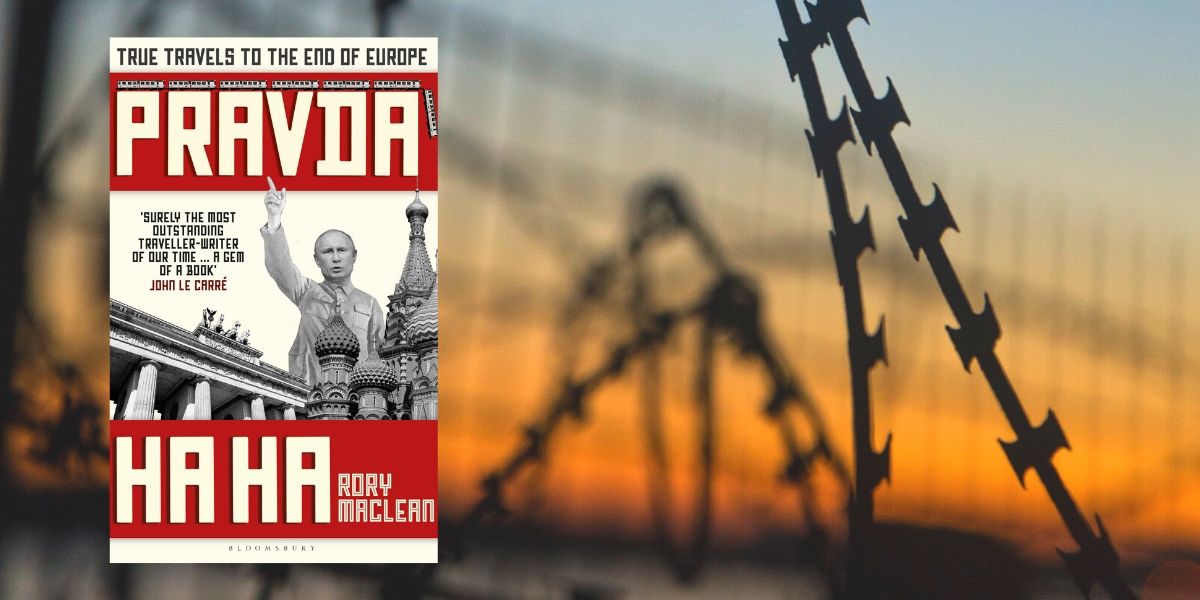

Pravda Ha Ha – True Travels to the End of Europe

Rory MacLean – a review by Jon Woolcott

In the final weeks of the 1980s, just after the fall of the Berlin Wall, writer Rory MacLean set off on an idiosyncratic journey across what he describes as the ‘forgotten half of Europe’. The resulting book, Stalin’s Nose, was hopeful, darkly comic and ground-breaking. It captured the optimism of the new decade and alongside Mandela’s freedom, it felt briefly as if we had achieved something approaching Fukuyama’s End of History. Thirty years on, MacLean retraces his steps, this time in reverse, examining the rise of Putin’s crony capitalism, the reassertion of old enmities and the attendant populist nationalism across the region. Jon Woolcott reviews the brilliant and troubling Pravda Ha Ha.

MacLean isn’t like other travel writers; his reliance on his own senses and experiences produces a series of powerful hyper-real but realistic vignettes. MacLean renders the East as a series of other-lands, not quite like us, but close enough. Everyone is fascinating and has a story to tell. This humanity and adventurous spirit give his writing power. Threaded through this journey is Sami, who we first encounter in a dream-like sequence in a railway carriage on the Moscow underground when a bird alights on Sami’s shoulder. A Nigerian, he’s washed up in Russia having been the victim of people trafficking with one of his fellow refugees dead from suffocation in the back of a truck. MacLean tries to help, offering money, food, even a bed for the night. He also emails a travel editor to pitch a piece on cruise ships, hoping he might be able to get Sami onboard a boat leaving St Petersburg.

Sami’s plight is affecting but it’s far from the only bleak part of Pravda Ha Ha; considering recent Russian history and that of its former satellites, how could it be otherwise? We hear of a Hungarian who hanged himself while on the run from a labour camp and a meeting with sinister alt-right would-be media moguls who drink Bordeaux and offer MacLean exotic foods. There are almost unimaginable horrors – death and torture in a former gulag-cum-monastery, under the Tsars, Bolsheviks and Stalinists. MacLean points out that the Russian church has often colluded with the State and its influence is pernicious.

MacLean is a charming and idiosyncratic guide to the East but he’s also sharply astute. Whilst attempting to visit Gorbachev’s former Dacha in Crimea he’s confronted by a soldier who blocks his path. Putin had long coveted the Dacha, and Crimea in general, and the rumour is that the Russian President is in residence. MacLean reflects on Gorbachev’s legacy – well-intentioned, compassionate but, without the established institutions of democracy, bound to fail. He’s excellent on the rise of Putin, previously an obscure KGB functionary, whose wealth is now believed to be greater than arch-capitalist Jeff Bezos. He visits the anonymous building from where, it is thought, Russian hackers manipulate Western democracies. The technology is new but the aim is the same as it was for the Leninists – to sow discord. His meeting with ex-hacker Alina is chilling. Previously employed to post on the message boards of UK telecoms companies to polarise political opinion, she says of her own country that “people are again becoming used to being silent, to accepting rules.”

In Estonia he meets a military officer who was once charged with defence against Russian aggression. Knowing they could never win a war fought conventionally, instead the Estonian army learned from the long insurgency against the Soviets: hiding in woodlands, disrupting supply lines and terrifying the Red Army. The rise of populists is laid out starkly however: in Hungary’s leader, Orban, especially, MacLean identifies a leader prepared to do anything, blame anyone, especially the tiny population of Muslims, to cling to power. In Hungary he meets the son of an old friend, down on his luck, and accompanies him to the town’s outskirts at night to drink with other homeless men, all of whom blame outsiders for their misfortune. Here MacLean loses his rag, telling them they’re wrong, his argument enflamed by their unthinking and simplistic assertions as much as their home brew booze. Pravda Ha Ha is crammed with episodes like this, in which he traipses to the modern heart of darkness but in case we feel too smug or lucky, he draws parallels with the rise of populism in the West, and at the end of the book meets one of the new breed of ‘disaster Capitalists’ – ready to exploit instability wherever in the world it occurs.

At the end of the book we meet Sami again. He’s made it to the UK and is now a bookkeeper for a reclusive owner of a fish and chip shop who lives amongst model railways and Airfix kits. For MacLean, these toys are representative of a Britain suffocating under nostalgia. But here at last is hope. The fish and chip shop owner has recognised that he needs the likes of Sami, whose determination and intelligence has kept him alive on his long and dangerous journey through countries in upheaval – countries which now differ greatly from the vision that many of us, Maclean included, had for them thirty years ago.

Rory MacLean is the author of more than a dozen books including the UK top tens Stalin’s Nose and Under the Dragon as well as Berlin: Imagine a City, a book of the year and ‘the most extraordinary work of history I’ve ever read’ according to the Washington Post. He has won awards from the Canada Council and the Arts Council of England as well as a Winston Churchill Travelling Fellowship, and was nominated for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary prize. He has written about the missing civilians of the Yugoslav Wars for the ICRC, on divided Cyprus for the UN’s Committee on Missing Persons and on North Korea for the British Council. His works – which have been translated into a dozen languages – are among those that ‘marvellously explain why literature still lives’ wrote the late John Fowles. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, he divides his time between the UK, Berlin and Toronto.

Jon Woolcott is a writer who lives in north Dorset. He’s researching and writing a book about the hidden and radical histories of the south of England, explored by bicycle.

Under Moscow

Pravda Ha Ha - Chapter 1

Underground there was no horizon. Underground the people moved in halting steps, moved as one, moved four abreast to ride down, deep down beneath the city. The earth swallowed them, corralled them, unnamed them as the metallic shriek rose up to strike them dumb. No one talked above the whine of the motors. No one stood out. Once or twice the odd traveller dared to shout, leaning towards his fellows, his warm breath brushing their ears. Otherwise the mass – ten million souls every day – moved through the deafening noise, unable or unwilling to be heard.

I stepped among them, shuffled with them down the banks of escalators to the platform. In the pale milky light waited office clerks and stallholders, weary shop cleaners and crisp police recruits, pedlars with sacks of tourist tat and widows in frumpy Soviet dresses who’d seen their sons shot dead in the chaos after capitalism’s triumph. Two hundred feet below ground the surging crowd elbowed aside a frightened, almond-eyed Yakut woman. Three white policemen approached her, backed her against the wall, demanded identity papers with a gesture that needed no words. Another traveller, a sharp-nosed Uzbek with his furious moustache, shepherded his young son around them without a look. The boy carried a plastic Russian flag. The scream of brakes echoed off the cold Crimean marble.

At peak times the trains arrived every minute at every one of Moscow’s 224 underground stations, grating to a stop, flinging open their gaping doors, sucking in the bydlo. That’s what Moscow’s elite call the common people, the countless commuting offspring of provincial peasants, the rabble from the city’s margins who’ll never stand tall, never escape the shadows. Bydlo. Proles. Cattle. Scum.

At Taganskaya the throng heaved itself off the platform, carrying me with it into the metal carriage, crushing me against three identikit blondes. The women – slender and curvy with violet nails and long straightened hair – batted me away with their lashes. A buffed twentysomething in T-shirt and jeans carried his crumpled security guard uniform in a plastic bag. Beside him a grey-haired, grey-skinned academic noted his earnings in a diary, a leaky biro stain on his threadbare pinstripe. On a seat behind them a bricklayer at the end of his shift squinted at two ancient Nokias nestled like matchboxes in his big hands, his sausage fingers punching out the wrong number on one of them again and again.

Then I saw the bird.

It came out of nowhere, flying in through a closing door, inches above our heads. It was starling-sized and short-tailed with buff- grey plumage. As the train accelerated out of the station, I guessed that it had flown down into the underground – above the escalators’ deep rolling rumble – and become trapped. Two men tried to grab it. The identikit blondes shrieked and ducked their heads. A stocky youth in bow tie began to swat at it with a folded newspaper. Other passengers held his arm, started to laugh, to yell, gazing in awe at the beautiful, frightened creature as it swept back and forth through the snaking carriages, shitting on the head of the failed academic in its terror.

Next the strangest thing happened.

After half a dozen fast flights, somewhere between Taganskaya and Kurskaya, the bird realised that there was no escape. Quite suddenly it stopped flying, and perched on a young man’s shoulder by the door. He seemed to be a random choice, not distinctive at first glance, neither handsome nor bad-looking either: slight build, tracksuit top and high, chiselled cheekbones under deep brown eyes. Not exceptional at all, apart from his stack of hair, his unruffled calm, and being black in Moscow.

The man’s stillness, and the frailty of the bird’s trembling chestnut breast, brought a sudden serenity to the carriage. Commuters stared at the astonishing sight, met each other’s glances, took hardly a breath so as not to break the spell, oblivious to the rising squeal of the brakes as the train slowed to pull into the next station. When the doors opened no one moved, until the man jerked backwards out of the carriage and onto the platform. Then the bird took off, its long flight feathers flashing with red and yellow tips.

I stared as well, before shaking myself out of my reverie. I wanted to follow him, to get off the train. I searched for my voice. ‘Are you getting off now?’ I said, pushing against the blondes. Vy seichas vykhodite? Let me off. But no one heard me, no one looked up as the crush of incoming passengers blocked my exit, entombing me again. Too soon the doors slammed shut and both man and bird were gone. With a scream the train plunged back into a darkness beyond which there was no horizon, no distant hill, no grand shadow cast in sudden valleys, only longsome tunnels that led from sleep to work and back again, day after day, night upon night.

Pravda Ha Ha is published by Bloomsbury.